The Cemetery:

'Welcome to Sanctuary Wood Cemetery - The wood got its name in November 1914 as it offered some cover to British troops a few kilometres behind the front line in Geluveld. By May 1915, the fighting moved to the edge of the wood but the name remained and lives on in infamy. It is also around that time that the first burials took place here.

During the war, three cemeteries were opened on the edge of the wood. All were severely damaged during the Battle of Mount Sorrel in the summer of 1916. Part of one of these cemeteries was found again and formed the nucleus of the present Sanctuary Wood Cemetery. The fact that some of the graves could still be identified is thanks to the Talbot House founder Reverend Neville Talbot who put together the very first cemetery register.

The location of the original walled cemetery, which only contained 137 graves, can still be made out amongst the scattered headstones at the far end of the cemetery. In 1927, more graves from closed nearby cemeteries were added, bringing the total today to 1,989 graves of which only 642 are identified.

If you walk towards the Cross of Sacrifice, keep an eye out for a solitary headstone in Plot I, Row G. This is the final resting place of Lieutenant Gilbert Talbot.

Gilbert's Story:

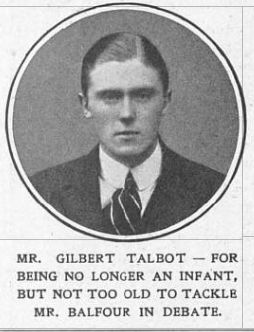

Gilbert Walter Lyttelton Talbot is born in Leeds on 1 September 1891 as the youngest of a family of five. Mother Lavinia Lyttleton is of noble descent and father Edward Stuart Talbot is the vicar of Leeds Parish and is on the brink of an impressive career which will bring him to the dioceses of Rochester, Southwark and Winchester.

As a child he is noted for his fun, no nonsense, and love of beauty. When his older brother Neville goes to fight in the South African War, eight year old Gilbert thinks it is fascinating. “He could have stood a cross examination in all the battles, small or big, and in the generals and heroes on the Natal side of the fighting“.

As a youngster, he has a sharp mind and excels at debating. In 1909, he matriculates at Balliol College, Oxford, where he chairs the Oxford Union. His energetic speeches catch the eye of politicians such as David Lloyd-George. He is a founding member of the Young Conservatives and is even earmarked to make it to Prime Minister one day.

At Farnham Castle, the Bishop of Winchester’s residence, Gilbert finds calm again. The peaceful scenery, the old keep and beautifully kept gardens make an everlasting impression on him. He will often call these to mind when serving at the front.

On 31 July 1914, Gilbert and his friend Geoffrey Colman embark on a nine month long world tour. Whilst crossing the Atlantic, war is declared. They have barely spent six hours in Quebec before they return home to fulfil their patriotic duty. Both young men enlist in the local regiment, the Rifle Brigade, a popular choice as Gilbert’s brother, Chaplain Neville, and his uncle, General Lyttelton, had worn the same cap badge.

After the officers’ training course, he is put in charge of a platoon of C Company, 7 Rifle Brigade. His colonel tells him: “Remember you are in charge of 54 lives, not 55 – don’t count your own.”

Thoroughly convinced of the just cause of war, he writes home on 3 September: “Whatever else is true of life, one thing is certain – that I am doing the right thing now and that every ounce in me must go to it till the end.”

The transition of the easy-going college life to the tough military discipline isn’t straightforward. His orderly ‘Appy’ Nash remembers: “His first morning on parade was rather amusing; the platoon lined up and he inspected us; faint smiles on the faces of the boys. He then told us what he expected from us; 'first obedience to orders, we must be properly dressed, clean, shaved, spruce and smart. Then there were more giggles. Puzzled, he called me aside and asked the cause of this. I had to inform him that his cap, with peak and badge, should be facing to the front, his tie should not be holding his left ear up, and that tapes on his puttees were for tying up. I let him see himself in a mirror and he was shocked!”

Slowly but surely, he takes to the military life. His results on the rifle range however leave something to be desired, hitting Nash’s target rather than his own. This he related at Mess that night and caused much merriment and leg-pulling. At Christmas, he twice takes his men to entertain them at home at Farnham castle. On 18 May 1915 he goes home for the final time to bid goodbye to his parents.

The next day, the battalion crosses the Channel and spends the night in Boulogne. But home never drifts far from Gilbert’s mind. “At times one’s thoughts fly back to all the precious things in England, a thousand times more precious now. I think of Farnham, Winchester, Oxford in summer. And one thinks of all the family and the happy times we’ve had – the love that binds us all, and Mother and all she is to me, and I don’t feel ashamed of wondering fairly often if I shall see them again, and if so when.”

Soon Gilbert goes into action on some of the famous ridges in Flanders. At St Eloi he ends off burying several of his men and at Hooge he encounters underground warfare. His brother Neville serves as Senior Chaplain to the 6th Division so the two are able to meet up at times.

On 17 June 1915, Gilbert visits the ruins of Ypres. It leaves a lasting impression on his mind. “I despair of telling you what the place looks like. It beggars description. The suburbs of the town are comparatively intact, though most houses there have been shelled. But the whole inside is simply a desolation. You cannot imagine it being rebuilt. We walked through the streets and found not one house which was not a mere mass of ruins or just a big heap of bricks. And then we came into the famous Place. The Cloth Hall, roofless and ruined, lies all the way down one side, and the Cathedral is just beyond it. As everywhere else in the town, there’s not a living soul to be seen, except passing British soldiers. We wandered through the Cloth Hall and saw the fragments of the famous frescoes. I didn’t go into the Cathedral till the next day. It’s not quite as big as Southwark and must have been very lovely. Now it’s got no roof and there are huge holes in the walls, and the aisles are heaped high with fallen masonry. Nothing has brought the war home to me as has this town. Its people had no connection with the war, no interest in the war, and their lovely home has been gutted until it’s unrecognizable. I wish everybody in England could see it. Harry and I remembered that the last expedition we made together was to Oxford. I tried to think of the peace and loveliness of Magdalen and Christchurch on that May evening and to contrast it with the blackened ruins we were now seeing.”

A few days later, Gilbert and his men march through Poperinge on their way to Zwynland to get a bath, his first hot bath since leaving home. Maybe he passes what is soon to become known as Talbot House…

By 28 July, Gilbert is back at Hooge, a very hot place indeed. A few days earlier, the British blew an underground mine and advanced their line to the spur of the hill. Everyone now fears the German retaliation. That night he writes to his brother Neville: “We’ve had a hell of a time at Hooge, it’s certainly the deuce of a place. It’s very trying, and we’ve had a lot of nervous breakdowns. Come and see me when you can.”.

The next day, on 29 July 1915, the 7th Battalion, with Lieutenant Gilbert Talbot, is relieved by their friends from the 8th Battalion Rifle Brigade. Gilbert’s batman reports: “On July 29th when the party had marched half way back to Vlamertinghe, about 8 miles, we all lay down at once by the roadside about 3.30 a.m. About two hours later I was roused, and was told the Battalion was to return to make a counter attack on the crater, which had been vacated by the 8th Battalion, owing to their being attacked by unexpected use of liquid fire. I called Gilbert who was up at once, and after the first sleepy moment was in very good spirits as we walked off after only a cup of tea – scarcely any food. Some had bits of chocolate and biscuit with them. The last hour or so, Gilbert and me walked on alone ahead of the rest – shelling became more violent as we got nearer to Zouave Wood." Gilbert said to me: “We’re going up all together to a warm shop. I don’t suppose many of us will come back.”

The 8th Rifle Brigade had suffered a severe blow by the new German flamethrowers. One of Gilbert’s close friends, Lieutenant Keith Rae, was last seen standing on the parapet of his trench, covering the retreat of his men as he was engulfed in flames. The front line was surrendered and the British found themselves at the bottom of the hill, looking up to what today is the Hooge Crater Cemetery.

"The condition of Zouave Wood was unspeakable – trees with no leaves left had fallen from shells like spillikins one over the other, and there were corpses, and wounded men, and huge pits and horrors and desolation beyond description. We all waited from 2 to 2.40 while our side bombarded – to which the Germans answered furiously – and many were killed and wounded in the wood. At first Gilbert went up and down, cheering the men – but at last no words could be heard, so great was the noise, and he went and sat a little apart, on the right, with his head a little bent. I think he was praying hard. He looked constantly at his watch. At 2.45 he blew the whistle which was the signal to charge – and at once the men – only 16 were now available – leapt out, and rushed forward, Gilbert, followed closely by myself, headed them a few yards on, with the words “Come on my lads – this is our day.” Soon he came to the old British barbed wire fencing, which he was beginning to cut, when he was hit in the neck, and fell over the wire fencing. I was badly hit in the left arm, at the same moment as my master, and dashed forward, wrenched out his bandages, and turned Gilbert gently on his back, and tried to bind up the fatal wound in his neck. His blue eyes opened wide and he saw me and gave me a bright smile, then turned a little over, and died. While my right hand was on Gilbert’s breast pocket to lay him down a bullet pierced the third finger (it was afterwards amputated) and went right through Gilbert’s cigarette case and, I suppose, through his heart."

Some of the trenches lost earlier that night along the Menin Road, have now been regained. But the centre of the attack is cut down; few men get further up the slope than Gilbert. Their bodies are left in no-man’s land as the Rifle Brigade has to retreat again. Despite being badly wounded, Nash offers to go back with a few stretcher bearers. More than one team gets close but the German fire is too dangerous. More men are wounded and the colonel forbids further attempts. Nash would later be awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal and would keep a close link with Toc H and Tubby for the rest of his life. He would often return to the battlefield as a pilgrim.

Neville Talbot learns of the attack and sends a telegram to the colonel of the battalion. The reply he gets is not what he had hoped for. “I am afraid there seems no doubt that Lieutenant Talbot was killed. One man in his Company states he saw him fall while leading his platoon through some wire and is certain in his own mind he is dead. All efforts to find his body failed.”

On 1 August 1915, Neville arrives at Zouave Wood and is set on bringing back his brother’s body: “I remember seeing the remains of the shattered Rifle Brigade – after they had been relieved: dear Colonel Ronnie MacLachlan in tears over the loss of all his ‘boys’. It grew dusk, and I made up my mind to crawl out the necessary thirty yards. The German trench in front, which was being shelled, was by then 150 yards away, I think. I went, on hands and knees, lying flat as the flares went up. I first found the body of young Woodroffe VC and there, just past the wire, lay Gilbert. It was very hot weather, and, of course, the bodies were much affected by it; it was rather horrid. I took his cap badge and some things out of his pocket. He was lying almost on his face, obviously killed outright. I stroked his hair and commended his soul to the Father, to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, and prayed that we might meet again, and crawled away. I couldn’t have buried him and I couldn’t very well carry him in."

On 7 August, Neville goes back and with the assistance of a few men from the East Yorkshires, he is able to pull in the body. Neville buries his brother in the recently opened Sanctuary Wood Cemetery. A sapper makes a wooden, cross and Neville writes ‘a word of Peace’ on it.

Several months later, as the well-known story goes, Neville is asked for his chaplains to open a club of their own in Poperinge. The initial name for their home from home, Church House, is quickly dismissed and replaced by Talbot House. It honours the golden generation of young men who did not return and remembers in particular Gilbert who with his 23 years had a bright future still ahead.

The House bearing his name opened its doors on 11 December 1915 and continues its mission to this day. Neville would continue to visit his brother’s grave, and at least twice during the war he had to put a new grave marker up.

In 1924, the cross is replaced with the current Portland headstone. The wooden marker would later be put into the Upper Room at Talbot House as a memorial. The headstone bears the epitaph: “In Lumine Tuo videbimus lumen”. Or ‘In Thy light shall we see light’, derived from the wording on the Toc H Lamps.

On 13 December 1924, the ninth anniversary of Talbot House, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales gives light to a Toc H Lamp in memory of his friend Gilbert. Despite his young age, Gilbert had a wide range of friendships, including the future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Lord Balfour, who said of him: “I loved Gilbert, he was always delightful to me, and I cherished the most confident hopes that if he tried he could do great things for his country. He has done great things – the greatest and most enviable – but not in the way I expected.”

General information:

Name: Lieutenant Gilbert Walter Lyttelton Talbot

Date of death: 30 July 1915

Age: 23

Origin: Winchester

Regiment: Rifle Brigade, 7th Battalion

Buried: Sanctuary Wood Cemetery I.G.1

Epitaph: Fear not I am he that liveth – In Lumine Tuo videbimus lumen

Link to Talbot House: The House is named in his memory. He came to been as a symbol of the sacrifice of a Golden Generation - Please note the Talbot House rose at the back of the headstone. The rose was planted on the centenary of the death of Gilbert Talbot. [This special type of rose was created to mark the centenary of the House and is available at Talbot House for purchase.]