Named Henry but always known as Harry, Sapper H Jack was born 7 August 1887 in the Parish of Bonhill, Dunbartonshire, Scotland. He was killed in action on 5 October 1917.

Harry’s father John and mother Elizabeth (nee Lumsden) were brought up in Fife, the children of farm labourers and domestic servants. Harry had an older brother Robert, and younger sister Catherine.

They moved to Glasgow where John worked as a Coachman in service to rich families living in large houses around the Kelvinside area of the city.

Census records show the Jack family living in Mews accommodation (stables with living quarters above) including at Woodside Place Lane and Park Terrace. Living in that area, Harry and his siblings had the extensive Kelvingrove Park as their playground.

Harry would have been 14 when the 1901 Glasgow International Exhibition was held in Kelvingrove Park including the opening of the new Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. His sister Catherine recalled the many wonderous exhibitions, pavilions and entertainments which were on their doorstep over that summer.

Harry became an apprentice carpenter and his woodworking tools, some embossed with “H.JACK”, have been handed down as a legacy through Catherine’s family.

When his father died suddenly in 1906, the family moved to Napiershall Street in Glasgow with Harry subsequently working as a time served carpenter/joiner to help support the family before the outbreak of war.

Harry was posted to the Royal Engineers where his professional skills and experience would have been put to good use. We have little detail of his war service other than that he served in France and Flanders and that he was perhaps one of the Tunnel Companies constructing tunnels to aid troop movement to and from the front.

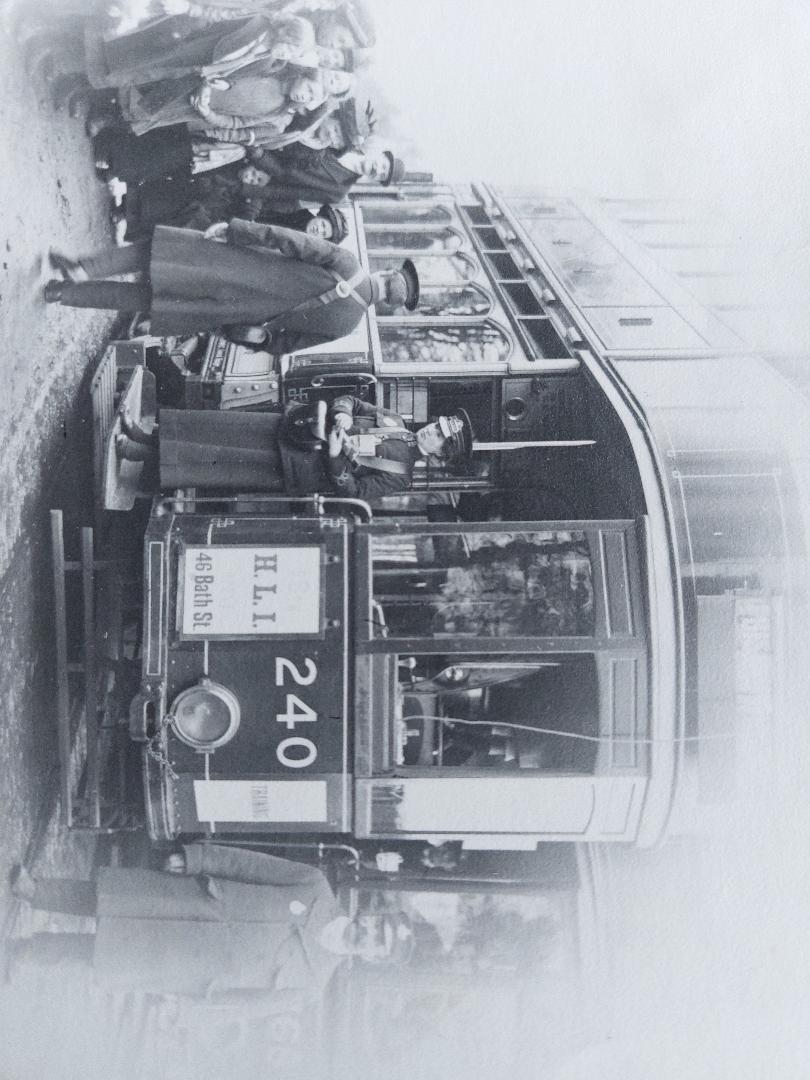

Catherine supported the war effort at home by working as a tram conductress in Glasgow, one of the many traditionally male jobs ably performed for the first time by women at that time.

Harry was loved by his family and his death was deeply mourned. His sacrifice was never forgotten, and Catherine passed affectionate memories of her brother through her children.

Subsequent generations still think of “Uncle Harry” at times of national remembrance with his apt epitaph “he died that we might live”.